The cicadas are loud this year. Quite loud. At least they are where I live in Pudong. Their sound, which is almost indescribable – not a buzz, more a pulsating chatterous skeez – fills the air day and night. The high point came a couple weeks back when they set up a truly deafening, almost three-dimensional roar. They are trailing off now. Day by day the sound thins, like the tide going out leaving small islands here and there. Soon there won’t even be islands – just silence. Now there are are only a few left. You probably won’t even notice they’re gone, just like you barely noticed they were there. How can something so loud be so invisible?

There are thousands of species of cicada around the world. They are found on every continent except Antarctica. Most are annuals – meaning they re-appear every year. A famous few are periodicals which appear on 13- or 17- year cycles. Tracking the periodicals has garnered a cult following. Various theories have been put forth to explain the evolution of the periodicals. Stephan Jay Gould, probably the most famous evolutionary biologist of the 20th century, theorized that prime numbers gave the cicadas an advantage over predators.

There are thousands of species of cicada around the world. They are found on every continent except Antarctica. Most are annuals – meaning they re-appear every year. A famous few are periodicals which appear on 13- or 17- year cycles. Tracking the periodicals has garnered a cult following. Various theories have been put forth to explain the evolution of the periodicals. Stephan Jay Gould, probably the most famous evolutionary biologist of the 20th century, theorized that prime numbers gave the cicadas an advantage over predators.

Male cicadas are responsible for the noise. The sound is their way to attract mates. Females lay eggs in small slits in the tree bark. The eggs hatch and the offspring emerge from the bark, then fall down to the ground where they burrow in the dirt among roots, emerging 2-17 years later as “nymphs”, millions at a time, at which point they climb the nearest tree, shed their exoskeleton and achieve the adult form that is most familiar to us – stubby body, flat head, folded wings. Cicadas are one of the largest common insects. Megapomponia imperatoria measures an astonishing at 7 centimeters. Even still, you can barely make them out in the foliage. Aside from a few husks on the ground, the only evidence of presence is their incredible sound.

And it is truly an amazing sound. Legendary. Inimitable. Huge. Alien and yet so completely familiar. It reminds me of summertime in Indiana where I grew up. Hearing them in Shanghai set up their racket makes the world seem less strange.

Cicadas have been around for millions of years. Fossil evidence dates back to the beginning of the Cenozoic era. They have proven remarkably adaptable to the modern world, easily exchanging the temperate forests of yore for the xiaoqu of today. Even more astonishing – they are not regarded as pests. They don’t eat ravage crops. They don’t kill trees. As far as insects go, they are surpassed perhaps only by the butterfly for cultural status. They have literally provided the soundtrack for human evolution.

Cicadas have been around for millions of years. Fossil evidence dates back to the beginning of the Cenozoic era. They have proven remarkably adaptable to the modern world, easily exchanging the temperate forests of yore for the xiaoqu of today. Even more astonishing – they are not regarded as pests. They don’t eat ravage crops. They don’t kill trees. As far as insects go, they are surpassed perhaps only by the butterfly for cultural status. They have literally provided the soundtrack for human evolution.

Cicadas were well known throughout human history and were a source of fascination in ancient Greece and ancient China. They make their first appearance in western literature courtesy of Homer’s Iliad. Aristotle described the life cycle of the cicada in his book Historia Animalium. But cultural evidence of cicadas in culture dates back to the 2nd millennium BC in ancient Mycenae. A thousand years later, in ancient Athens, cicadas appeared on local coins. Thucydides tell us that Athenians had taken to wearing gold ornaments in the shape of cicadas as a way of showing citizenship – of properly belonging to a place and therefore capable of owning land.

The cicada’s most enduring cultural symbolism is rebirth and, by extension, immortality. Both ancient Greeks and ancient Chinese were known to put jade sculptures of cicadas into the mouths of deceased for burial. The hope was that the amulet would aid in reincarnation. It’s not too difficult to imagine the practice being inspired by observation of cicada nymphs emerging from the ground after long periods of quiescence.

This became a powerful trope, especially in China. The main character from Journey to the West – the monk Xuanzang – is named as the 10th reincarnation of the Golden Cicada, a relative of the Sakaymuni Buddha. In the book it was believed that anyone who ate Xuanzang’s flesh would live forever, a fact which precipitates most of the adventures and misfortunes that befall them on their journey to fetch the sacred scriptures, a journey which, by the way, in reality was as much to heal a divided and disintegrating Tang dynasty, as it was spiritual.

This became a powerful trope, especially in China. The main character from Journey to the West – the monk Xuanzang – is named as the 10th reincarnation of the Golden Cicada, a relative of the Sakaymuni Buddha. In the book it was believed that anyone who ate Xuanzang’s flesh would live forever, a fact which precipitates most of the adventures and misfortunes that befall them on their journey to fetch the sacred scriptures, a journey which, by the way, in reality was as much to heal a divided and disintegrating Tang dynasty, as it was spiritual.

In Journey to the West the connection between Xuanzang and the Golden Cicada is explained by Buddha himself:

“释迦如来佛亲口点点说来: 圣僧,汝前世原是我之二徒,名唤做金蝉子。因为汝不听说法,轻谩我之大教,故贬汝之真灵转生东土。”

It is interesting to note that Buddha here is called 如来佛, or Tathagata Buddha. “Tathagata” is generally understood to mean “one who has thus come”, which is consistent with the Chinese “如来” This is a very complex term. People generally see it as indicating someone who has broken out of the cycle of karma (death and re-birth) and thus “arrived.” The well-known 5th century Buddhist scholar Buddhaghoṣa, meanwhile, interpreted it in relation to truth, seeing it as “one who has arrived at truth”. But it intrigues me to consider another angle – “Tathagata” is also the name that, in the sutras, Buddha often uses to refer to himself, a stand-in for “I” or “me.”

By doing so, Buddha essentially swaps singular for the plural. It’s not an uncommon rhetorical strategy. In the Bible we find plural nouns like “Elohim” used to describe God. In China there is the very interesting case of the first person pronoun zhen (朕) which Emperor Qin Shi Huangdi appropriated for himself and forbade anyone else to use. In the 12th century, the first usage of the “royal we” was officially recorded in the court of King Henry II.

In each case a plurality is created from a singularity with a concomitant shift in subjectivity. In Qin Shi Huangdi’s case, he is saying, “I am everyone – so much so that you are not even you anymore.” In Henry II’s case he is saying, “I represent everyone.” In the Buddha’s case he suggests each of us is the same because each of us has the potential to “arrive” at truth.

Edward Conze, one of the foremost translators of Buddhism in the 20th century, saw it that way, writing, “Just as tathata designates true reality in general, so the word which developed into ‘Tathagata’ designated the true self, the true reality within man.”

Try it yourself. Every time you want to say “I”, replace it with “One who has thus come.” People will think you’re strange, but it’s an important rhetorical shift – from me to multitude. And it is this spirit that lays at the heart of Journey to West, China’s most enduring myth cycle.

Cicadas are equally important to western thought. They form a critical – if overlooked – element of Plato’s dialogue between Socrates and Phaedrus. Socrates prefaces their discussion with:

Cicadas are equally important to western thought. They form a critical – if overlooked – element of Plato’s dialogue between Socrates and Phaedrus. Socrates prefaces their discussion with:

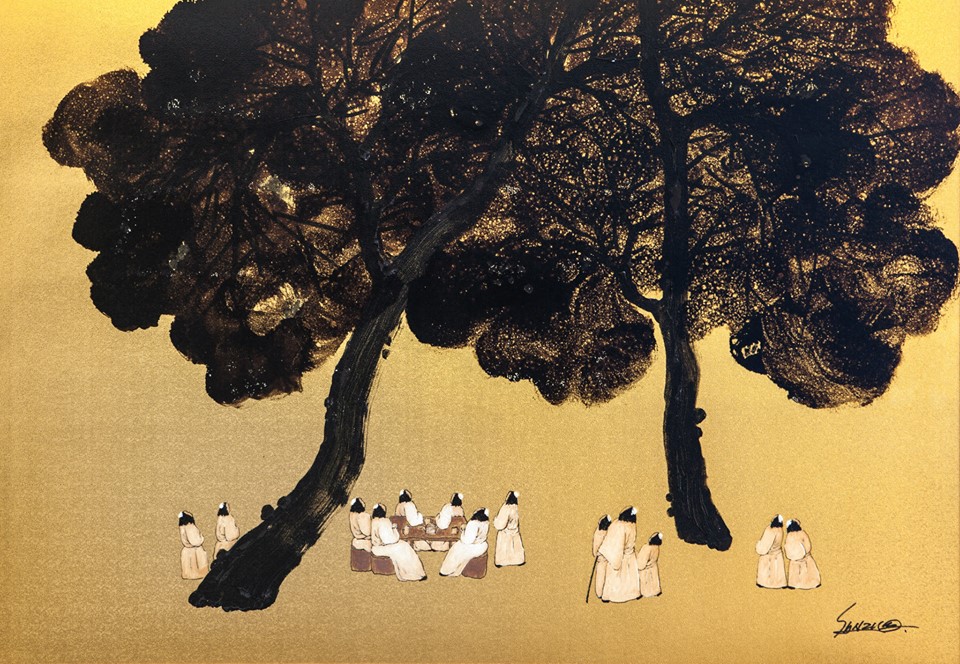

“By here, a fair resting-place, full of summer sounds and scents. Here is this lofty and spreading plane-tree, and the agnus cast us high and clustering, in the fullest blossom and the greatest fragrance; and the stream which flows beneath the plane-tree is deliciously cold to the feet. How delightful is the breeze – so very sweet; and there is a sound in the air shrill and summerlike which makes answer to the chorus of the cicadae.”

Cicadas come up again in a later interlude with Socrates saying to Phaedrus:

“A lover of music like yourself ought surely to have heard the story of the cicadae, who are said to have been human beings in an age before the Muses. And when the Muses came and song appeared they were ravished with delight; and singing always, never thought of eating and drinking, until at last in their forgetfulness they died. And now they live again in the cicadae; and this is the return which the Muses make to them-they neither hunger, nor thirst, but from the hour of their birth are always singing, and never eating or drinking; and when they die they go and inform the Muses in heaven who honours them on earth.”

Most commentators overlook this detail. Understandably – it seems a minor background point. The main drama of this notoriously complex piece is love – both physical and spiritual. But more than that it’s about speech, more specifically the problem of love as provocation for speech. Love is not simple inspiration for vocalisation, it’s a response to its powerful tides and irreducible complexities. If you’ve ever been in love, you know what I mean. You wail as much as you sing.

University of Manitoba Classics professor Rory Egan sees here the connection to cicadas, writing,

“It is unlikely to be an accident that in the popular belief of the Greeks and in their poetic conceits the cicada has strong associations with both eloquence and with the erotic and that the cicada should also be so prominent a feature of this dialogue. The reason for the former association obviously has to do with their conspicuously strong and musical voices, while the association with Eros must stem from observation of their copulation (also described for us by Aristotle) and perhaps from deducing that their singing had a sexual function. This sort of eloquence and eros is of course strictly on the sensate, physical level, but the cicadas of the Phaedrus are not, I think, mere flesh and blood entities.”

Cicadas are inspiration for how we can conceive of ourselves and our place in the world. They are not mere backdrop, but vivid symbols. A friend of mine who studies Zen Buddhism sees them as an esoteric symbol of mastering the life force (usually expressed as sexual energy). I see them as a symbol of how we can get along with each other and the world. There are billions of them, endlessly adaptable in the face of change, coming every year yet basically harming nothing. Each individual sings for all it’s worth for the short time it has and together they make a chorus that’s as unique as anything anywhere.

Cicadas are inspiration for how we can conceive of ourselves and our place in the world. They are not mere backdrop, but vivid symbols. A friend of mine who studies Zen Buddhism sees them as an esoteric symbol of mastering the life force (usually expressed as sexual energy). I see them as a symbol of how we can get along with each other and the world. There are billions of them, endlessly adaptable in the face of change, coming every year yet basically harming nothing. Each individual sings for all it’s worth for the short time it has and together they make a chorus that’s as unique as anything anywhere.

What ails us these days? What is killing hope? Between greed on one side and anger on the other there is a great enabling silence. One voice alone will do nothing except be a martyr. So much better if our songs link up into a deafening roar of individual expression. It’s the message cicadas have sent us every year for millions of years, so loud and clear that it’s nearly inaudible.

Beyond that, a final question – what of the last cicada of the season? What does it mean to be the last voice on the branch with no mates left to attract and no songs left to accompany? What’s it like to be the last one singing? This year I will listen more carefully. I want to hear the song of the last cicada. I want to know if it’s any different than any other. I think it might be.

And then I want to hear it stop.

Oh, my, such good stuff, researched, eloquent, educational.