Uncanny silence has surrounded Scott Savitt’s memoir since it was published in November last year. Though National Geographic and Vice both recommended it, there was no New York Times review, no big book tour, no NPR interview, no Literary Festival headlining slot. The local expat rags didn’t even pick it up which is surprising considering Savitt was for many years a well respected foreign correspondent and afterwards basically started what we now know as expat media in China. Why the lack of attention?

It’s not because the book is bad. Quite the opposite – it’s actually pretty great, fast-paced and energetic. Some parts read like a thriller with seriously pulse-pounding action. It covers 17 years – 1983 to 2000 – in less than 300 pages.

It’s not because the book is bad. Quite the opposite – it’s actually pretty great, fast-paced and energetic. Some parts read like a thriller with seriously pulse-pounding action. It covers 17 years – 1983 to 2000 – in less than 300 pages.

And it’s certainly not for lack of historical significance. Savitt was witness to and participant in post-Cultural Revolution China’s most important events – the birth of Chinese rock ’n’ roll, the emergence of the Yuanmingyuan Artist Colony, the arrival of the internet, Tiananmen Square – the whole sweep of gaige kaifang essentially. He also hung with heavies like Cui Jian, the playwright Cao Yu, Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo and former U.S. ambassador Winston Lord to name but a few. He even rode in a limo with Nixon for a day.

In fact I can’t see why his book isn’t getting more attention. Maybe he pissed off the wrong people. Who knows? Anyway, it’s solid. More than solid. I rate it right up there with Simon Leys’ Chinese Shadows, Theroux’s Iron Rooster, Jean Pasqualini’s Prisoner of Mao and Hessler’s River Town as one of the best post-Liberation China memoirs.

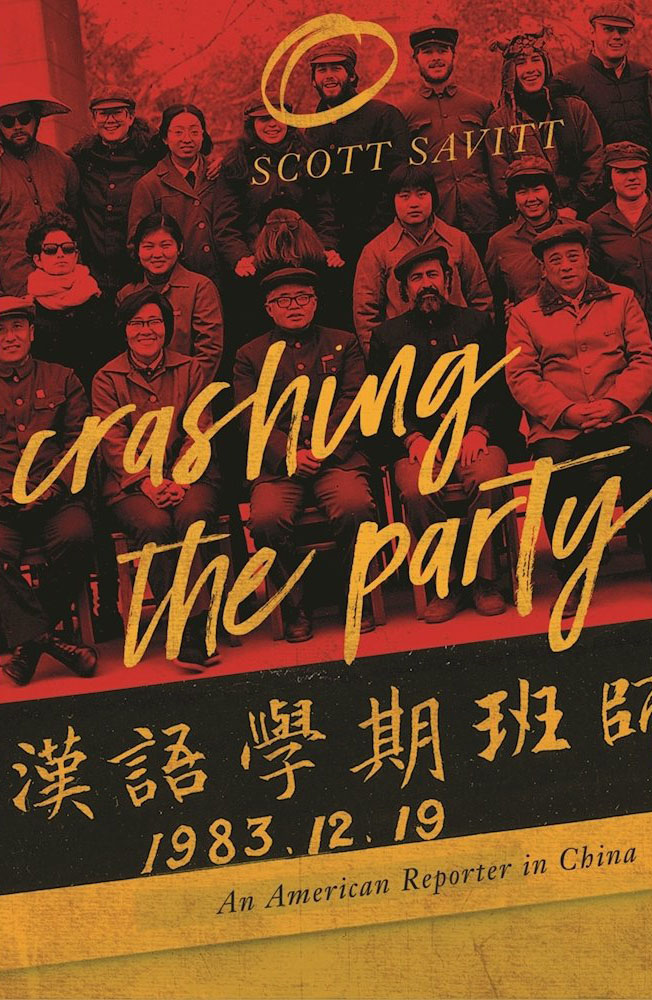

The book starts out with a punch in the gut – Savitt laying on the floor of a Chinese prison – before whipping back to his first day in Beijing as a foreign student in 1983. By chapter 4, death makes its first appearance and you know this isn’t going to be a “Do you know how to use chopsticks?” fish-out-of-water farce.

The events of Tiananmen Square take up the biggest chunk of the book. It’s been covered well many times before, but Savitt takes us to places no other writers ever have before. He was out in the streets the night shit got real – not just the streets, but west Beijing where the bulk of the killing took place. He saw the bodies. They fell around him. He had rifles pointed at him, “but” he writes, “for some reason they didn’t shoot.”

Sandwiched around that you get the bildungsroman of a young man’s rise to something like fame and his eventual downfall. Along the way he becomes the youngest accredited foreign correspondent in China, sets up an internet business and launches now legendary Beijing Scene magazine. But it all comes crashing down in the summer of 2000 as he’s frogmarched onto a United Airlines flight to San Francisco in handcuffs, never to return. We never really find out why.

If it sounds serious that’s because it is serious. There’s death, violence, broken hearts, broken people. There’s a lot of personal pain that comes through. Savitt seems like a pretty serious guy, suffused with a volatile mix of youth, idealism and talent, in a place and at a time that really had no idea what to do with him. A little more nyuck-nyuck and he would have been bigger than Dashan. A little more bookishness and he would have been the next Orville Schell. A little more materialism and he would have been very rich. Instead – and to his credit I think – he ends up a martyr to a moment when Human Rights truly warranted capital H and capital R, before it became a quaint sideshow to the main business of greed.

Maybe that’s why he hasn’t gotten the attention. Grapple with his story and you have to grapple with just how unfashionable the whole human rights thing has become. We used to care so much about it – Westerners and Chinese alike. Where the hell did all that go? Was it just a fad after all like friendship beads and Pokemon Go? Even this guy’s story which made the rounds this month failed to move the needle much.

For expats, of course, the book offers an invaluable window into Beijing of the ’80s and ‘90s. His recollection of the Cui Jian headlining the Halloween bash at Maxim’s is a classic example. I used to cycle past that shithole in Chongwenmen shaking my head and thinking, “How could that have ever been the coolest place in Beijing?” Now we know.

I wish the book had more of that – ambiance I guess you would call it. But then the book would have been 2 or 3 times as long. Which would have been fine with me. I mean seriously, Proust published 10,000 pages of nothing much happening. Savitt’s memoir could easily have been split up into several volumes, each with a different flavour. But what it lacks in background detail it makes up for with a surfeit of action. Maybe it is a curse to live in interesting times after all.

And that’s the thing for people who, like me, came to China a bit later. The days are long gone when you could walk down the street and end up starring in a TV show, or show up at English corner and meet the cultural vanguard. It just doesn’t work like that anymore.

The times still are interesting, of course, but now you have to make an effort. You have to spend the time and be open. You have to observe closely and dig beneath the surface. If China has succeeded in anything in the last two decades, it’s wrapping everyone in a comfortable illusion of normalcy. But along the edges of that, battles still rage. And they aren’t just battles of the mind.

A big reason that you failed to address is because it was published by Soft Skull Press, an indie pub not recognized by Big Media, who incestuously only review books put out by their pals in Big Publishing. And since Savitt’s book has no big media blurbs, this in turn results in disinterest from literary reviews who won’t bother with a title “if nobody else has.” Moreover, Big Media are indeed now absolutely petrified of upsetting Beijing, and even the whole China Watcher scene now prefer to pander to the Party than speak out against it. I could be wrong, but I haven’t seen any of the usual Sino-tastemakers mention Savitt’s memoir or offer to host him on their podcasts/platforms, so there could be some bad blood dating back to the Beijing Scene magazine days. And if they won’t tweet about the book, then second-tier twitterati who take their cue from the Sino-twaterati cabal certainly won’t either. As I’ve discussed frequently on Reddit, it’s a profoundly cliquey scene and far more complicated than what you could even begin to touch on in your review of this fine book.

Dear White Confucius: Thank you for this insightful review. I think you struck a chord with: “Instead… he ends up a martyr to a moment when Human Rights truly warranted capital H and capital R, before it became a quaint sideshow to the main business of greed.” It pains me to read your following paragraph: “Maybe that’s why he hasn’t gotten the attention. Grapple with his story and you have to grapple with just how unfashionable the whole human rights thing has become. We used to care so much about it – Westerners and Chinese alike. Where the hell did all that go? Was it just a fad after all like friendship beads and Pokemon Go?” I came of age in 1980s Beijing. It was a much more hopeful, idealistic time. I just tried to capture some of that optimistic spirit in my writing. Of course everything changed—for me personally but I argue for Beijing and China—on June 4, 1989. That was the seminal experience of my life, and I believe it’s still the specter that haunts the Party and the real third rail of Chinese politics. No wonder nobody wants to talk about it. I was the Expat Mayor of Beijing in my day. A big frog in a shitty little swamp. 真人不露相, 露相不真人. In the 1980s there was no such thing as an Expat Mayor (we all did read Geremie Barmé’s weekly column in the Far Eastern Economic Review) because the real heroes were the Chinese writers/reporters/artists/activists we were documenting. That all changed after the Tiananmen Protests/military crackdown, and pretty much everyone reading these words has known only post-六四 Beijing/China, where being a p.r. flack for a state propaganda organ or selling a censored internet entity is considered admirable/courageous. Too much history has been forgotten. Here’s a good short documentary that captures the spirit of the Beijing I knew.* I’ll conclude with this quote from Beijing poet/Democracy Wall activist Bei Dao: 在沒有英雄的年代裡我是想做一個人 “In an age without heroes, I just want to be a man.” * https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ho8vAFlCeFQ&list=PL90A1D34D81B78C75&index=6