I was depressed the other day. The kind of feeling where basically everything seems like shit and you don’t have any clue why you still live in China and, as a consequence, you are hateful toward everything. This is nothing to be alarmed about. It happens from time to time. When I fall into this state of mind, I know it is time to go back to basics and put some effort into remembering the good parts of being a foreigner here. In this case, that led me back to Edward A. Burger.

Burger is a documentary filmmaker I met in Beijing in 2006. We were introduced by a mutual friend and shared hot pot on Guijie. I had been told he was a filmmaker, a claim I was skeptical of myself having just come off a year at the Beijing Film Academy. I figured if he were serious about it, he would be there too and know the people I knew.

The evening must have been cordial, because I remember very little about it. I find that dinners are only remembered when either salad gets dumped on your head or you end up having a first kiss – anything in between gets forgotten. After dinner we parted and, because there was no Wechat back then, immediately lost touch.

Several years later – 2009 I think – I was looking through a DVD shop (remember those things?) when I came across a documentary titled “Amongst White Clouds: Buddhist Hermit Masters of the Zhongnan Mountains”. The case showed the classic China misty mountain thing and bore the filmmaker’s name: Edward A. Burger. I bought it.

The funny thing is that I didn’t connect the film to the person I had met. For starters, that person had been introduced to me as Ted, not Ed. And second, I didn’t recall us talking about Buddhism, hermits, the Zhongnan Mountains or this film. I bought it because as a thwarted Sinologist I’m a sucker for documentaries about China. I watched it one Friday night alone in my apartment. I was blown away.

The funny thing is that I didn’t connect the film to the person I had met. For starters, that person had been introduced to me as Ted, not Ed. And second, I didn’t recall us talking about Buddhism, hermits, the Zhongnan Mountains or this film. I bought it because as a thwarted Sinologist I’m a sucker for documentaries about China. I watched it one Friday night alone in my apartment. I was blown away.

A digression – there are many very good documentaries about China. Check out this page if you don’t believe me – it’s the tip of the iceberg. But they are hard to find. Usually you have to know people in that scene even to hear about them and getting a chance to view them is another matter entirely. Actually I think it is less about censorship by the authorities than the fact there’s hardly any market for documentaries – a real shame.

Of all the wonderful China documentaries, only a handful were made by foreigners. I’m thinking of Morning Sun and Gate of Heavenly Peace by Carma Hinton and Geremie Barme, Chung Kuo by Antonioni and the BBC pre-Olympics nature doc Wild China. Amongst White Clouds is up there.

To condense it into a sound bite, it’s River Town if Hessler had been a Buddhist adept rather than an English teacher. Towards the beginning of the film, we catch the filmmaker packing books into a rucksack then cutting across the sprawling plaza of Beijing Zhan on his way to catch a train to Shaanxi – one of those old classic green ones. The year is 2003. This is accompanied by Burger’s voiceover filling us in on his backstory. It’s a little vague but we understand there’s a book of poems involved and the search for a master.

This is enough to get us to the Zhongnan Mountains where we meet Burger’s master. We follow him around his mountain temple as he tends crops and drops gems of wisdom in thick Shaanxi-accented Chinese. From there we move on to meet other hermits living on the mountain, all at different places in the journey to enlightenment. Some are old, some are young, some are impossible to tell. Burger talks to each one about life, death and the things of this world and in doing so he delivers a series of poignant sketches. Interspersed throughout are shots of nature – some beautiful, some intimate, some obscure.

Towards the end Burger manages to meet to a recluse rumoured to be very far advanced in his practice. The last 10 or 15 minutes are all about him. The film ends with shots of Burger hiking out of the mountains back into the world of men with the monk’s final words as voiceover accompanying him. It’s a poignant way of reminding us that in the end this film is about Burger’s journey.

And that’s okay. It’s nothing to be ashamed of. It’s honest. It’s no reason to dismiss the film no matter what the post-colonial pencil pushers might have to say. Burger’s Chinese is excellent. His interactions with the monks are genuine. The translations into English of what the hermits have to say is very well done. Overall it’s much better than this rather awkward 2015 offering from Red Pine himself which is also about the hermits of the Zhongnan mountains (Red Pine is the laowai who “discovered” the hermits 25 years ago).

But what I admire most is that in seeking his path, Burger does what very few foreigners do nowadays: he takes Chinese people for teachers. He allows Chinese people – men specifically – to be guides along the way. It’s inspiring stuff for people like me who, even after decades, are still looking for the right way to live in this adopted land.

I re-watched the film. You can find the whole thing on Youku and Youtube. It did the trick, levering me out of whatever black hole of self pity I was in. I put the phone down and got observant again – the color of the sunlight on the leaf of a tree, the particular speckled pattern on the tile of the floor, the looks on people’s faces in the metro, clumps of snow on a bush. Things started to come to life again.

I conceived a grand project. I would take a bunch of video with my phone and stitch it all together in thematic sections with wildly pretentious titles like “Sunny Days” / “Places with Good Music” / “Introduction – The Why” / “Green & Gold” / “Commuting” / “Alienation / “Work” / “My Son” / “Evening” / “How It Will All Turn Out”. I would pen Terence Malick-esque lines for a voiceover. My friend Graeme would edit the whole mess into a sublime work of staggering genius. Over the course of a few days I made some fevered notes.

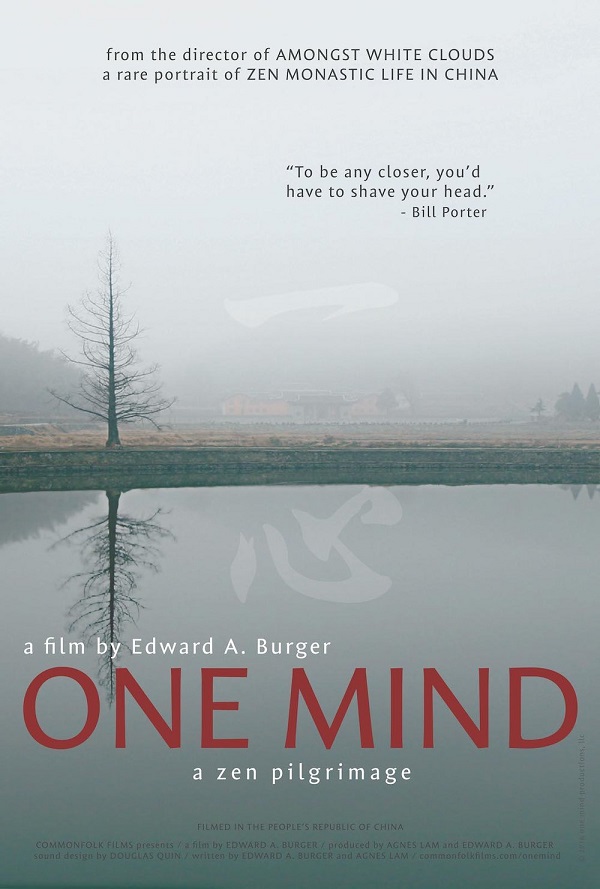

In the meantime, I wondered what Ed was up to, what had become of him. I took to the internet and discovered he’d continued making films and, in fact, had just completed a new one in the summer of 2017. It’s another Buddhist themed documentary called One Mind, shot in a Zen monastery in Jiangxi. In an interview Burger said he wasn’t trying to make a film about Buddhism, but rather a Buddhist film. I was intrigued. I thought with great confidence, “This is going to be good.”

I got in touch with his distributors and they very kindly arranged for me to watch it online. They were, I think, hoping that I would be able to organize a screening of it in Shanghai. This could be done. I’m sure I could probably get a couple dozen people to show up for it. But the screening wouldn’t work. It would be a failure. People just wouldn’t have the patience for it. They would start squirming and looking at their phones within 10 minutes.

I got in touch with his distributors and they very kindly arranged for me to watch it online. They were, I think, hoping that I would be able to organize a screening of it in Shanghai. This could be done. I’m sure I could probably get a couple dozen people to show up for it. But the screening wouldn’t work. It would be a failure. People just wouldn’t have the patience for it. They would start squirming and looking at their phones within 10 minutes.

Burger has taken himself out of the story entirely. What’s left is an austere mixture of the extremely mundane and the extremely ethereal with a lot of close-ups of monk’s faces in between. There are long scenes of monks having their heads shaved, cutting bamboo, picking tea leaves and making dinner in huge woks. The little talking we get isn’t even about the path of enlightenment. Maybe that’s what enlightenment is all about.

It’s probably a great film. I don’t know. But I did learn this:

I am not yet enlightened.

——

PS – If you have some mad desire to see One Mind, add me on Wechat (leeallenmack) and let me know. If enough people are genuinely interested, I’ll try to set something up.

I’m a Soto Zen priest, and a retired English professor–the film sounds fascinating and I hope I get a chance to view it sometime.

from lat. manus – “hand” and scribo – “I write”) [1]