80 years ago this August the Battle of Shanghai began.

It wasn’t the first time war had come to Shanghai. It wasn’t even the first time that China and Japan exchanged blows in Shanghai. But it was the most devastating urban battle Shanghai – and the world for that matter – had ever seen. It was, as one historian remarked, as if Verdun had taken place in Paris just opposite a neutral Left Bank. It led directly into the Nanjing Massacre and kicked off a chain of events that culminated in World War II and ultimately the two nuclear bombs dropped on Japan. It was real bad news.

Why look back? Aside from the fact that the Chinese government is looking back (expect big time propaganda leading up to December 13, the 80th anniversary of the Nanjing Massacre), I don’t know, knowledge I guess. Before I read Peter Harmsen’s book Shanghai 1937: Stalingrad on the Yangtze, I had only the barest outlines of what went down. I was pretty shocked to realise that rivers of blood once flowed under our feet. It seems significant. Here’s what happened.

Most of the (surprisingly little) chatter so far has been about Paul French’s Battle of Shanghai cash-in, Bloody Saturday: Shanghai’s Darkest Day. This 100-page pamphlet reconstructs the events of August 14,1937, when bombs (dropped by Chinese pilots) hit the Peace Hotel and the Great World Amusement Park killing more civilians than at Guernica. That event grabbed the headlines, but the battle actually had started the day before – August 13 – at Baziqiao, Eight Character Bridge. The bridge was a key access point to Hongkou Park (now Lu Xun park), just south of which was the headquarters of the Japanese marines and the heart of “Little Tokyo.” This is where the first shots were fired.

This is Bazi Qiao today – not much left behind to commemorate the beginning of one of the bloodiest wars in modern history.

This is Bazi Qiao today – not much left behind to commemorate the beginning of one of the bloodiest wars in modern history.

The Chinese moved first trying to take the initiative. On August 14 they threw an elite division against the Japanese marine HQ, hoping for a quick, decisive blow. That didn’t happen. They met heavily fortified positions, well defended with machine gun emplacements. Things quickly devolved to bloody, building-to-building street fighting. Japanese fighters and bombers filled the air. Artillery aboard Japanese destroyers in the Huangpu opened up. Shells and bombs fell all over Hongkou and Zhabei. Over the next week, large parts of Hongkou were reduced to rubble.

The following week a second major attempt to push the Japanese into the Huangpu likewise failed. Meanwhile Japan began rapidly reinforcing Shanghai. On August 23 under cover of night several Japanese divisions landed on the south bank of the Yangtze near Wusong and Chuanshakou, opening up a new front. By the beginning of September, the Japanese had landed 40,000 troops. By the end of September that number had reached 90,000. The war escalated rapidly, engulfing the entire region.

80 years ago Zhabei and Hongkou were hardly more than a couple miles north to south. Between their northern border and the Yangtze River it was farmland, small villages and swamps connected by a webwork of canals. There were few bridges and fewer roads. One of the most important of those roads started from a town called Luodian and ran south all the way to the Shanghai train station. That was the prize the Japanese were after. Today that roadway still exists, the S106, or if you prefer – subway Line 7.

The Japanese methodically ground their way south from Luodian. Chinese regiments were wiped out to the last man as generals threatened court martial for any soldier who ran away even though there was no hope of winning. Civilians who got in the way were killed without compunction – shot, bayoneted, or beheaded. Bodies filled up the canals. Harmen’s book details graphic accounts of executions lifted from soldier diaries. He calls the cruelty of the Japanese “mind boggling”. The Chinese were hardly better, practicing a scorched earth policy as they organised retreat after retreat. The countryside was devastated.

By October 6 the Japanese had crossed Wusong Creek which, according to one account, ran red with blood. Liuhang was abandoned to destruction shortly thereafter and the line pulled back to Dachang – a medieval style walled village and the last significant barrier on the road. If it fell, Japanese armour would have unimpeded access to Suzhou Creek. For a week it was shelled and bombed until nothing remained of it except parts of the wall. One newspaper correspondent called it “the fiercest battle in Asia ever waged”.

These days Dachang is a just a stop on Metro Line 7, nothing in the suburban sprawl to commemorate 1937’s orgy of destruction, just a huge blue IKEA and a few quiet canals.

These days Dachang is a just a stop on Metro Line 7, nothing in the suburban sprawl to commemorate 1937’s orgy of destruction, just a huge blue IKEA and a few quiet canals.

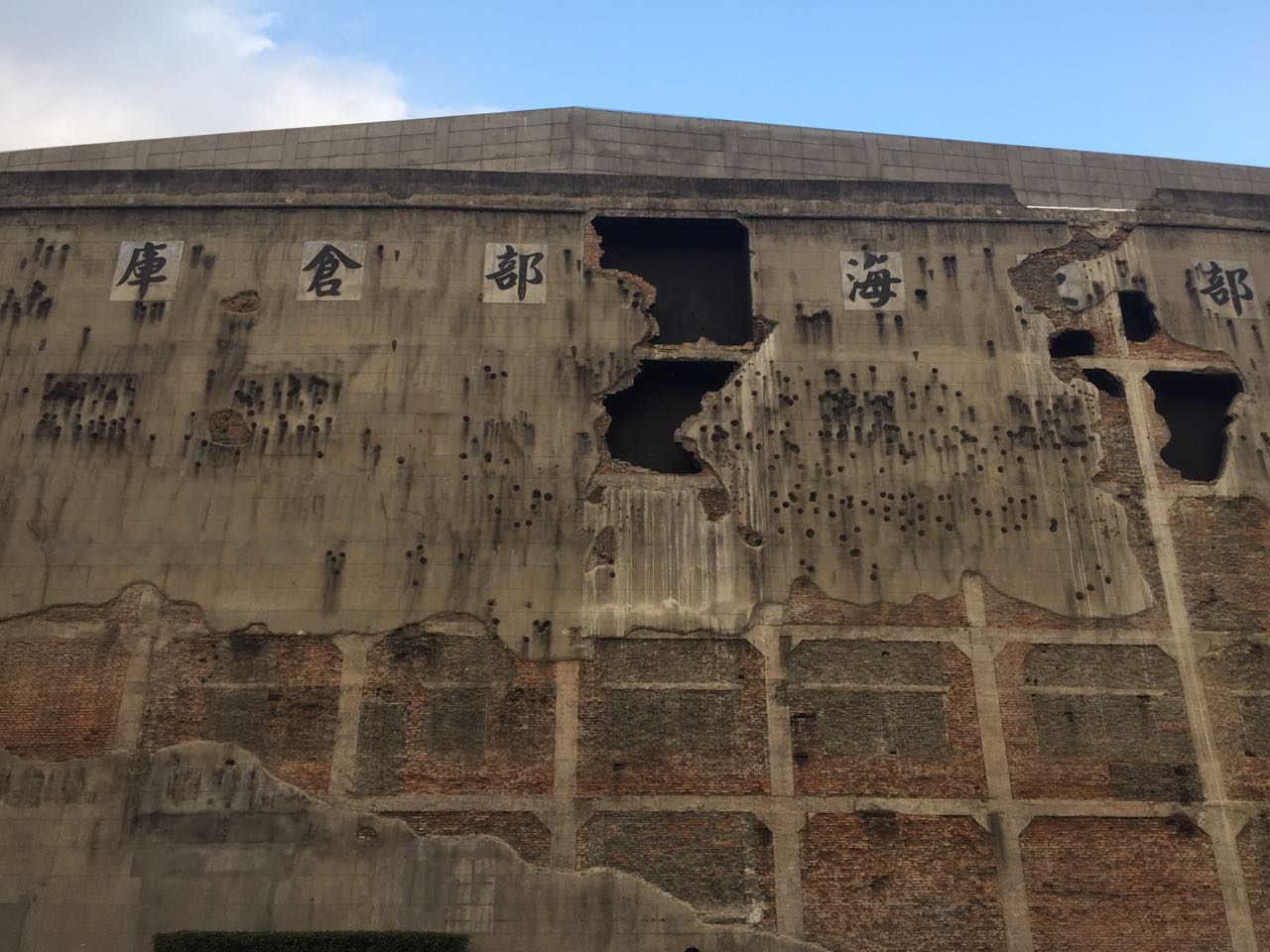

By the end of October the Japanese had reached Suzhou Creek. There was nowhere else for the Chinese army to go without giving up the city. Here was born a lasting legend of the Battle of Shanghai – the “Lost Battalion”. Essentially what happened was this – a battalion of troops was ordered to hold one final piece of territory north of Suzhou Creek, the Sihang Warehouse (Four Banks’ Warehouse), as a symbolic gesture meant to show the Chinese fighting spirit as well as to forestall the inevitable. They held out until the last day of October before retreating across Suzhou Creek.

The Sihang Warehouse is still there, just off Xizang Lu on the north bank of Suzhou Creek. It re-opened in 2015 as a museum honouring heroes. This wall, torn by shells and bullets, is all that remains of the original.

The Sihang Warehouse is still there, just off Xizang Lu on the north bank of Suzhou Creek. It re-opened in 2015 as a museum honouring heroes. This wall, torn by shells and bullets, is all that remains of the original.

After a week of seesaw battle along Suzhou Creek the Japanese tipped the balance by surreptitiously landing a large force on the north bank of the Bay of Hangzhou. They raced across the lightly defended countryside and easily crossed the Huangpu. The Chinese army was caught in a classic pincer move and, at that point, it collapsed completely. On November 9 the Chinese army began a chaotic retreat from Shanghai with the Japanese army in pursuit. On November 11 Shanghai officially fell. A month later Nanjing did the same. The rest, as they say, is history.

A couple of things to mention. First, the rape of Nanjing was not a one-off sort of thing. What happened in Nanjing had been happening throughout the path of devastation the Japanese army left in its wake which essentially included the entire Shanghai peninsula – from Jinshan to Baoshan – home to more than 4 million people. Read the Harmsen book, it’s all there. Babies were not spared. Old people were not spared. No one was spared. Except the foreigners.

And that brings me to a second point – the Battle of Shanghai was, in large part, a show instigated by Chiang Kai-shek for the benefit of the world. Chiang knew he couldn’t defeat Japan without help. So the Nationalists opened up Shanghai as a front hoping that it would embroil the world’s major powers. The presence of the foreigners was essential. Basically Chiang was trying to start WWII. He succeeded. Sort of.

Chiang’s obsession with the PR value of the Battle of Shanghai again and again caused him to demand incredible, ultimately futile sacrifices from his soldiers. The Sihang Warehouse soldiers became heroes, but in reality over half of them survived. Unremarked are the innumerable companies which were completely wiped out having been ordered to hold impossible positions.

Chiang spent their lives to gain days until the Nine Powers could convene a formal meeting in Brussels. He was banking on a declaration of war against Japan and a united front. When that meeting finally occurred in November 1937, China got nothing, just some League of Nations style hand-wringing. By then the battle was pretty much over anyway.

After the fall of Nanjing, it would be 4 more years before America got involved. That’s a lot of time. What happened? The Japanese army didn’t stop at Nanjing. It pressed further up the Yangtze to Wuhan which fell in 1938. Jiujiang, Xuzhou, Ji’nan, Anqing fell along the way. Changsha was torched. The capital of Free China moved to Chongqing.

Historian Stephen Mackinnon, who wrote the definitive work on this little-studied part of the war, estimated that 100 million people were displaced. All told in World War II 20 million Chinese civilians were killed along with another 3 or 4 million soldiers.

And it all started right here on our doorstep.